When I first started playing the guitar I remember how after a few months, once I’d learned my first songs, I noticed how certain chords tended to always go together – when a song starts on a G chord, there is usually also a C and a D at some point, and often an E minor, and maybe an A minor and B minor too. Similarly, when a song starts on a C, you usually find and F, G, A minor and maybe a D minor and an E minor.

As I learned more songs, these patterns and relationships started to subconsciously sink in and I gradually started to expect a C or D when I started on a G and an F, G or A minor when the songs started on C but I didn’t learn the reason why until years later – I wish someone had told me!

It’s easy to write off theory all together as boring and impractical, particularly when you first start playing and realise you could be using that time to learn a new tune, and theory is indeed often taught in a “user-unfriendly” way. If approached in the right way though a little bit of theory goes a long way and can be a true musical life saver, particularly when you are playing with others or find yourself trying to figure out a new song on the fly.

MUSIC THEORY MATTERS

Western music is broadly based around the sound of major/minor scales. These major and minor scales (which are closely connected, in fact the same set of notes played in a different order, but we’ll dig into how and why another time) are simply a series of seven notes characterised by the intervals, or space, between them (on a piano you can visualise these intervals as the numbers of keys in between notes or on a guitar the number of frets between them). You can think of these scales (again, simply a series of notes) as the ‘ingredients’ from which melodies and chords are built. The sounds of major and minor scales are instinctively recognisable in melodies like “Frere Jacques” or “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” (major scale) and the theme from “The Godfather” (minor scale). Every note in these melodies is contained in a major or minor scale so by learning these patterns on your instrument you will be much closer to learning to play them – all you have to do is figure out which order the notes are played in, which is much easier than you may think and is also great ear training!

Chords are closely related to scales and are defined simply as two or more notes played at once. From the notes of a scale (the ‘ingredients’ mentioned above) we can build a series of chords, which is referred to as ‘harmonising’ a scale. Let’s take the C major scale which includes the following notes: C, D, E, F, G, A, B. We can build the chords from this scale by starting on any of the seven notes and adding two more notes, skipping one note in between. For example starting on the C we would add the E (skipping the D which is in between) and G (skipping the F which is in between) – these three notes – C, G and E – make up a C major chord. Similarly if we start on D and then take F and A we get a D minor chord, and so on. We can give each of these chords a number depending on which note we start on: C is the ‘1’ chord, D the ‘2’ chord, etc. The 1, 4 and 5 chords are the most commonly encountered in pop/rock progressions, followed by the 6 minor, 2 and 3 minor chords. You may have heard of the ‘Nashville System’ which is used by pro players to write our song charts in recording sessions – the system allows them to quickly visualise the structure of a song regardless of what key it is in by replacing chords with the degrees they represent.

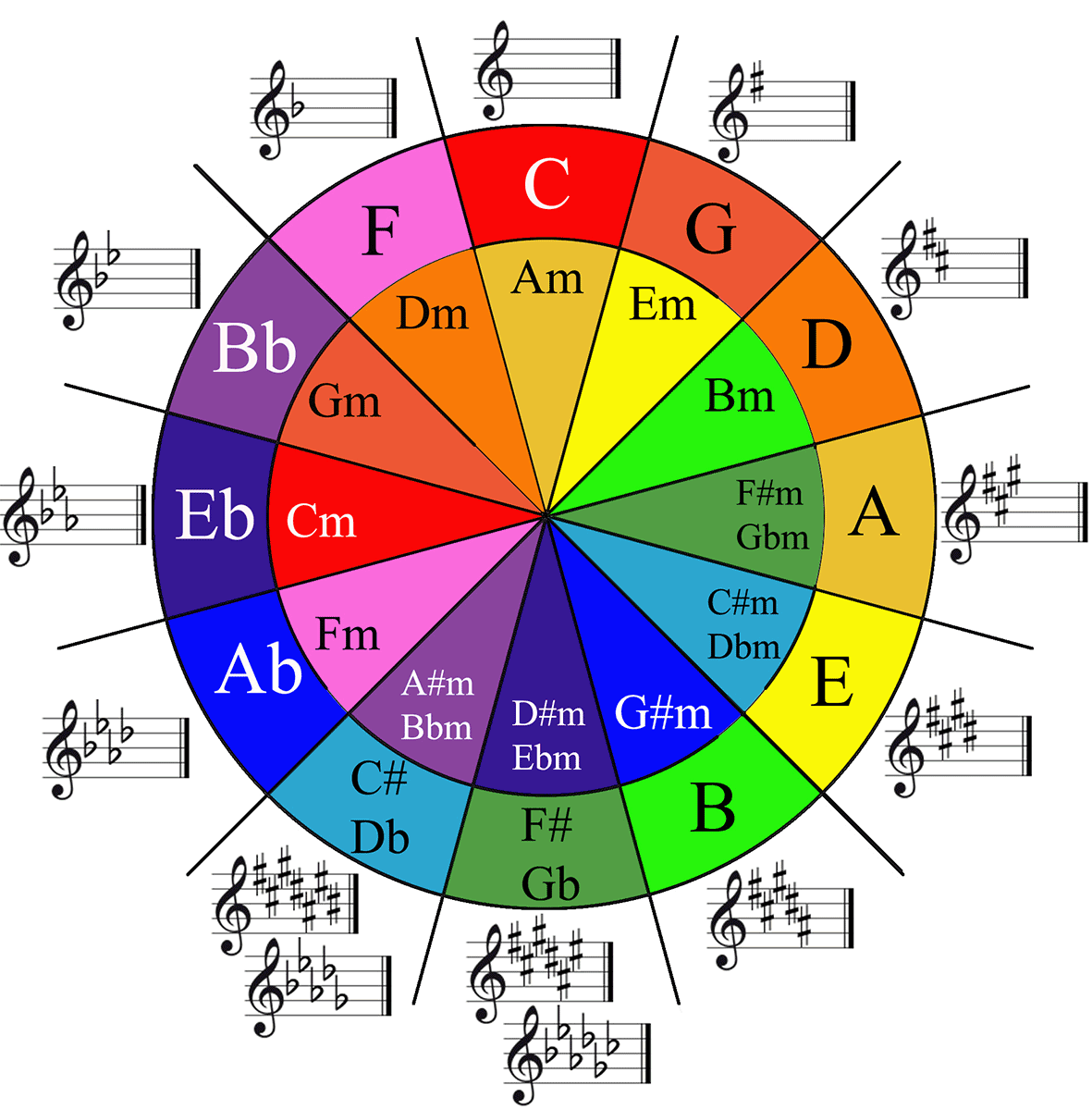

The important point is that, for reasons we’ll explain another time, this process of harmonising the major scale always gives the same pattern of major/minor/diminished chords in any key: 1 major, 2 minor, 3 minor, 4 major, 5 major, 6 minor, 7 diminished. So the chords in the key of C are: C major, D minor, E minor, F major, G major, A minor , B diminished. With a little practice, and the help of a ‘chord wheel’ (try googling it) you soon enough you will learn which chords are in each key. That, by the way, is not to say that you can’t have chords that are out of key – the Beatles and Nirvana were masters at throwing in off key chords such as a 3 major (E major if you’re in the key of C – very ‘Nirvana’) or a 4 minor (F minor in the key of C – very ‘Beatles’) which can be very useful musical devices to wake up the listener from a predictable pattern.

So, how is this useful? Imagine you are jamming with friends (or strangers!) on a song you don’t know and the only information you have is that it is in the key of C – you will immediately know that the most likely chords you will encounter are C, F, G, followed by A minor, D minor, E minor (and less likely, a B diminished), so you can try those. With practice (both playing and just as importantly listening) you will learn the specific sound of each chord degree. This is also a fantastic way to practice without your instrument – just listen to songs on the radio and try to figure out the chord progression – think of Twist and Shout or La Bamba, both 1-4-5 progressions, (C-F-G if we are in the key of C and G-C-D in the key of G) and then check out your guess with your instrument.

It’ll work, and quickly, I promise!